As of the end of 2018, the rate of employment of Arab women in Israel reached 40 percent, nearly doubling the percentage of this group in the labor force since 2003.[1] This rise is largely the result of concerted efforts to increase the number of Arab women in the workforce, which include a significant focus on enhancing access to higher education as a key factor. Among Arab women with degrees in higher education, 75 percent are employed.[2]

Today, largely due to the success of these efforts, Arab women comprise approximately 12 percent of Israeli undergraduate students, close to proportional with their representation in the country’s population. However, higher education is not the only barrier to employment for Arab women, and an academic degree does not guarantee employment. To better understand these barriers and help guide the growing number of Arab women entering higher education towards future employment, the Massar Institute in Jatt conducted a study of unemployed, educated Arab women.

The study, Unemployed Academically Educated Arab Women in Israel: Status Report for 2018 and Proposed Intervention Model, is based on a survey of 800 academically educated, unemployed Arab women as well as in-depth interviews with government officials, scholars in the employment field, employed and unemployed Arab women. The study was conducted by Prof. Khaled Abu-‘Asba, Head of the Massar Institute for Research, Planning, and Social Consultation, and was commissioned by the National Insurance Institute (Bituah Leumi) of Israel.

Its findings corroborate much of what had been previously established, but shed new light on these women’s perceptions, assumptions and motivations, and provide some surprising insights and new details. For instance, the study reaffirms that Arab women continue to choose fields of study that are not in high demand by the labor market, that lack of geographic proximity to jobs plays a key role in unemployment rates, and that Arab women from the south of Israel are disproportionately represented among those who are not seeking work at all.

However, it also points more specifically to lack of professional guidance and support for Arab women in finding work; the role of family influence on the choice of fields that today offer limited employment opportunities due to market saturation (i.e education); and widely-held perceptions that personal connections are essential to finding employment.

Following is a summary of the main findings and recommendations.

Survey Findings

In terms of overall perceptions and attitudes toward their careers, the academically educated and unemployed Arab women surveyed were career-oriented, with approximately 90 percent viewing a woman’s career as no less important than a man’s and reportedly aspiring to achieve “meaningful” employment. Additionally, the majority did not see income as the sole reason for seeking work and did not agree with the statement, “If the husband makes enough money, the woman does not need to work.” Nonetheless, most women surveyed were not overly willing to make compromises in their personal lives for employment advancement, and prioritized family over career goals. Therefore, the main struggle identified by the unemployed women was finding employment that would be both professionally fulfilling and conducive to their family commitments.

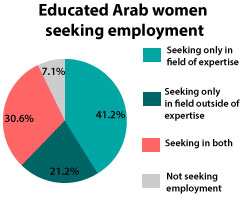

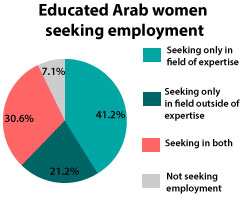

Survey results indicated that 72 percent of academically educated, unemployed Arab women are interested in working and are currently actively seeking employment in either their own field of expertise or another field. Only 7 percent of the women were not interested in finding employment in any field. The remaining 21 percent are only interested in finding work outside of their field of expertise and were not actively seeking employment at the time of the survey; half of this group named “exasperation with the job search” and “personal reasons” as the cause.

The vast majority of respondents, 86 percent, are married and most are also religious or traditional, particularly the Muslim respondents.

The study categorized respondents according to their job-seeking status as follows:

- Seeking employment in any field: 30 percent of respondents. Most of these women were younger than 30 and had graduated less than five years ago. Approximately one-third of this group were willing to delve beyond their field only if offered a full-time position.

- Seeking employment strictly in their field of academic expertise: 41 percent of respondents. This result shows that the majority of women did not regret their choice of academic expertise nor their academic studies, and were dedicated to their professional aspirations.

- Seeking employment strictly in fields outside of their academic expertise: 21 percent of respondents. Of this group, 85 percent were married and had graduated more than five years ago. This group regretted their choice of field of study to a far greater degree than did other respondents, and included more respondents from the south of Israel and relatively few women under age 30.

- Not seeking employment: 7 percent of respondents. In this group, more than 80 percent are married, 76 percent are 30 or older, and 72 percent are mothers. The percentage of women from the south of Israel was twice as high in this group as their representation among the educated, unemployed Arab women surveyed for this study, as was the rate of women who had graduated more than five years ago. Most women not seeking work were religious, some were traditional, and none were secular.

According to respondents, the most significant barrier they face in finding employment is the role of personal connections in securing work, followed by variables relating to the job market such as economic slowdown, competition, low wages, and lack of open positions in their fields of expertise. Proximity to the workplace is another prominent barrier, with Arab women finding it difficult to commute and forgoing remote job opportunities. Misalignment between training and open positions, along with over-qualification, were also cited as significant barriers, as was “lack of encouragement” within Arab society.

The most common job search method, utilized by two-thirds of the respondents, was sending resumes to potential employers. Other methods included job search via social networks, job listings in the press, and websites. Roughly 10 percent of educated Arab women take a more assertive approach and contact employers. Less than one-tenth of respondents rely on traditional methods such as depending on the help of their parents or government employment agencies to find work.

Interview Insights

The qualitative portion of the study was based on interviews with six government officials in the employment field, eight Arab researchers of the employment field, 20 employed academically educated Arab women, and 20 unemployed academically educated Arab women.

Some of the primary insights yielded by the interviews are as follows:

- The proximity of the workplace to the home appears to be the most crucial factor affecting Arab women’s employment.

- Families are prominently involved in women’s selection of study field, and often support the women during their studies. Women employed as teachers, pharmacists, and social workers reported that their families recommended these fields as they offer comfortable hours and geographic proximity to the home, despite being saturated market sectors in Israel.

- Finding employment in the education field is extremely difficult due to an over-supply of degree-holders in this field. In fact, Arab teachers in Israel suffer from rampant unemployment.

- Respondents mentioned no resources for employment-related guidance during and after high school other than their families, such as municipalities, government offices, or professional assistance, indicating that they lack access to such resources.

Government officials and scholars in the employment field noted many of the barriers facing Arab women that have been previously cited by studies on the subject (for instance, the Taub Center’s Arab Women Entering the Labor Market), particularly choosing fields of study that lack market relevance, low psychometrics exam scores, lack of mobility and willingness to commute long distances, lack of transportation and socio-economic development in Arab villages, and low capacities in Arab public high schools. Most government officials stated there was a clear policy to promote employment of Arab women in their respective departments, and mentioned government resolutions supporting employment integration, namely GR-922.

At its conclusion, the study makes several intervention recommendations for increasing employment among educated Arab women, some of which have existing precedent. These include:

- Legislative reform to ensure that a certain percentage of government employees are Arab women, and that government and public tenders be made specifically for educated Arab women.

- Full-time and part-time positions in government and civil organizations that take into account the characteristics and needs of Arab women seeking employment, such as hours, location and flexibility.

- Opening additional employment centers for occupational guidance and support, especially in the south, and including a focus on preparation for the job market, contact during the first few months of working in a new position, and connections with private and public sector employers.

- Entrepreneur workshops to help women develop initiatives rather than depend on existing employment opportunities.

- As the majority of educated, unemployed Arab women hold degrees in education or the humanities, the report recommends training and career change programs to assist in finding employment in sectors with more demand.

- High school workshops to expose Arab girls to career options with higher employment demand, and to help students select fields of study to prepare them for those sectors.

[1] Taub Center, Israel’s Labor Market: An Overview, 2018.

[2] Ibid.